ElmHistoryTools

One of the great aspects of the Elm programming language is its debugger. Because all the possible states of an Elm program are clearly defined and state only changes in response to messages, Elm can track everything that happens -- and make it available to you to debug both.

You can also export this history to a file, allowing your support team and developers to debug a user's session without having to be in the same room. Using a package like ElmRings, you can even capture this data automatically and upload it to your servers for later use.

Of course, once you have that data on your servers, you'll have to work through two challenges:

- Security: every keystroke of a user’s password and all the sensitive personal information they enter in your app go into Elm’s history. It’s no good hashing passwords on the user model if another table contains them in plain text — you need to sanitize and secure this data carefully if you store it.

- Complicated data structure: the Elm history data is meant to be imported into Elm more than it's meant to be analyzed by humans. If you want to show your support team what happened in a user session in which an error occurred, you need to make that data presentable.

If you, like me, have these problems, you're in the right place.

Installation

Add this line to your application's Gemfile:

gem 'elm_history_tools'

And then execute:

$ bundle

Or install it yourself as:

$ gem install elm_history_tools

Usage

Right now, ElmHistoryTools comes with two utilities:

Sanitizing History

Be careful you don't accidentally expose critical user information -- it's no good hashing passwords on the user model if an Elm history table contains them in plain text. Before storing

How do you actually do this?

ElmHistoryTools::HistorySanitizer allows you to sanitize Elm records and objects. Because these

objects are so individual to your application, there's no universal code that can sanitize the data

without breaking the structure. (This is why we can't, for instance, just use something like Rails'

ParameterFilters.)

Instead, you tell the HistorySanitizer which terms to look for and provide a block that can do the sanitizing:

# let's say you have an Elm object like

# MySecretData "access_token" {password = "myP@ssw0rd", expiration = "tomorrow"}

ElmHistoryTools::HistorySanitizer.sanitize_history(history_data, ["MySecretData", "password"]) do |elm_object_or_record|

if elm_object_or_record["ctor"] == "MySecretData"

# replace the access token

# make sure to return the updated object!

elm_object_or_record.merge("_0" =>"[FILTERED]")

else

# we have the record

elm_object_or_record.merge("password" => "[FILTERED]")

end

end

# before: {"ctor" => "MySecretData", "_0" => "access_token", "_1" => {"password" => "myP@ssw0rd", "expiration" => "tomorrow"}}

# after: {"ctor" => "MySecretData", "_0" => "[FILTERED]", "_1" => {"password" => "[FILTERED]", "expiration" => "tomorrow"}}

As you can see, this is neither flexible nor elegant -- unfortunately, that's the nature of the game when you're manipulating the state generated by an Elm program. Elm types may store sensitive data as basic data in the object, which leaves no automated way to detect and replace that information.

Format a History into a Hash

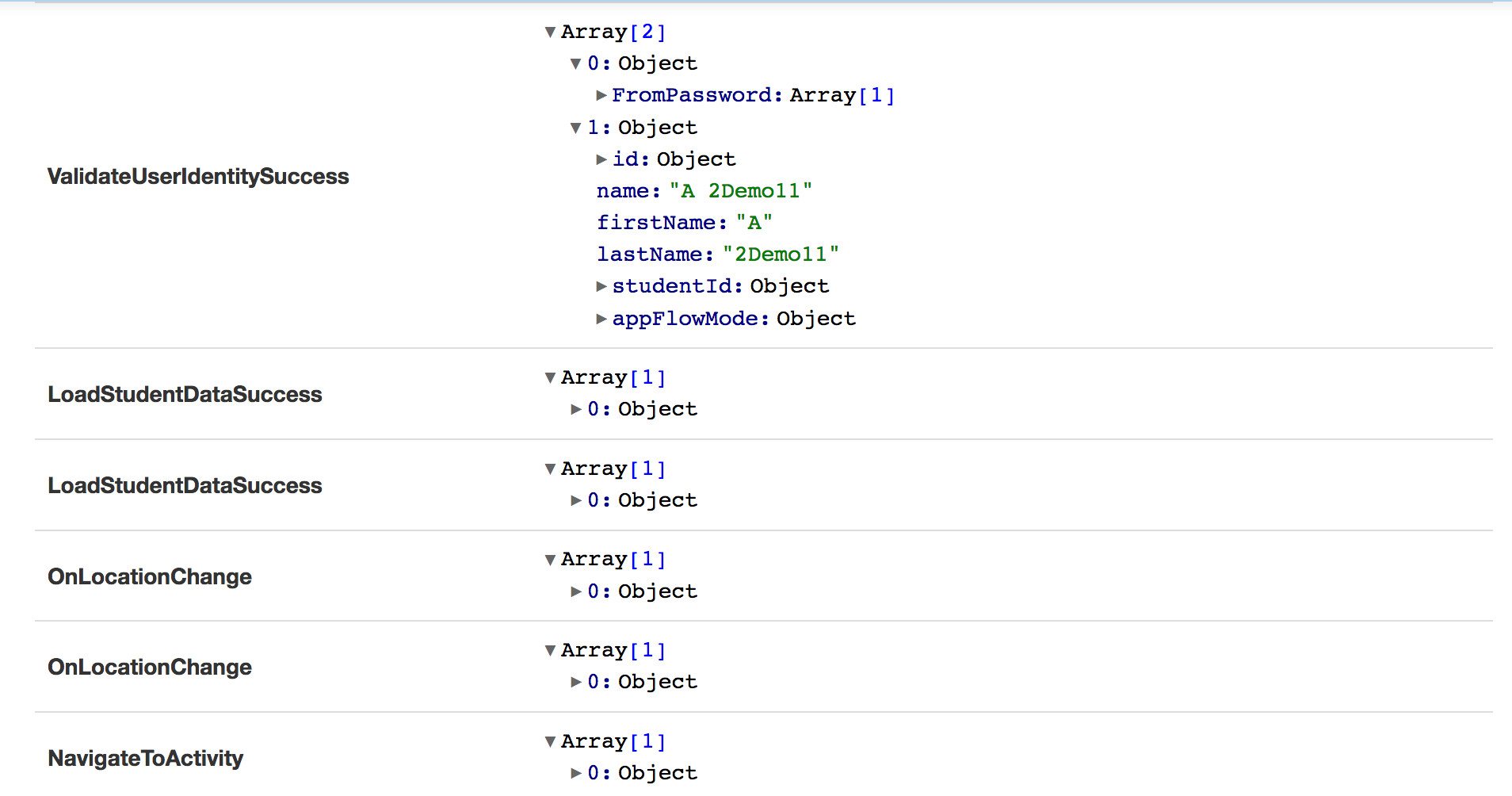

One approach we've found useful for user issues at eSpark Learning has been to skim the history and see if anything looks amiss. Eyeballing the user's actions shows if a student get an unhappy response back from a server, if they were able to they answer any quiz questions, etc., providing a useful context for further debugging.

In order to make sense of data, it has to be presented in a compact and (relatively) human-readable

format, which the raw history export is not. (See below for more information on that.) Such cleanup

is what the ElmHistoryTools::HistoryFormatter object can do:

# given a JSON history file like

# {"history": [{"ctor": "MessageType", "_0": "Arg1", "_02": {"ctor": "AnotherType"}}, {"ctor":"AnotherMessageType", "_0": "AnotherArg"}]}

ElmHistoryTools::HistoryFormatter.to_simple_hash(JSON.parse(history_json))

# will produce

[

{"MessageType" => ["Arg1", {"AnotherType" => []}],

{"AnotherMessageType" => ["AnotherArg"]}

]

You can then easily loop over this data in Ruby to present a readable internal dashboard:

Elm History Export Format

The Elm 0.18.0 history export is structured as followed:

{

"metadata": {

"versions": {"elm": "0.18.0"},

"types": {

// the Message type used by your program

"message": "Message.Message",

// all the type aliases defined in your program

"aliases": {

"Json.Decode.Value": {"args":[],"type":"Json.Encode.Value"},

// etc.

},

// all the union types used in your program

"unions": {

"Maybe.Maybe": {

// what arguments the union type takes

"args": ["a"],

// what tags/constructors make up that union type and what arguments they take

"tags":{

"Just": ["a"],

"Nothing": []

}

}

}

}

}

// what's happened in user session being exported

"history": [

// each entry is stored with the contructor and any ordered arguments passed to it

{"ctor": "MessageType", "_0": "Arg1", "_02": {"ctor": "AnotherType"}},

{"ctor": "AnotherMessageType", "_0": "AnotherArg"},

// etc.

]

}

Each entry in the history hash represents an Elm message object -- so

{"ctor": "MessageType", "_0": "Arg1", "_02": {"ctor": "AnotherType"}},

represents the Elm message

-- if type alias SomeType = AnotherType | SomethingElse

--

-- MessageType String SomeType

MessageType "Arg1" AnotherType

A few notes:

Lists

List entries are recursively nested objects whose constructor is :: (cons).

As an example, an Elm list of three books ([{title = "Too Like the Lightning"}, {title = "The Fear of Barbarians"}, {title = "Evicted"}]) would be represented as:

{

"ctor": "::",

"_0": {"title": "Too Like the Lightning"},

"_1": {

"ctor": "::",

"_0": {"title": "The Fear of Barbarians"},

"_1": {

"ctor": "::",

"_0": {"title": "Evicted"}

}

}

}

This is because in Elm, List is implemented as a linked list (each element is an object that both stores its value and points to the next element in the list, rather than sitting in an array of plain values).

You don't need to know anything about linked lists to use Elm (or Javascript or Ruby or, likely, whatever you're using for work or fun -- I've literally never used them in my career), but if you're curious, you can read more about them on Wikipedia. You can also check out this interesting discussion of Arrays vs. Lists in Elm.

In the future

It looks like the terms will change somewhat in a future version of Elm: "ctor" and "_01", "_02", etc. will be replaced with $, a, b, etc. ElmHistoryTools will support both formats in the future; should the structure change, obviously that will be addressed too.

Why hashes?

Why hashes?, you might wonder. Why not use arrays (e.g. {"MessageType": ["Arg1", {"AnotherType": []}]} or ["MessageType", "Arg1", ["AnotherType"]])? Wouldn't that be simpler?

Turns out you're not the first person to wonder about it. As @evancz wrote in response to a similar question in 2015:

I believe in the olden times, I did use an array because I just assumed it'd be fast. I later ran some benchmarks and was totally wrong, objects were a lot faster. So I switched everything.

Development

After checking out the repo, run bin/setup to install dependencies. You can also run bin/console for an interactive prompt that will allow you to experiment.

To install this gem onto your local machine, run bundle exec rake install. To release a new version, update the version number in version.rb, and then run bundle exec rake release, which will create a git tag for the version, push git commits and tags, and push the .gem file to rubygems.org.

Contributing

Bug reports and pull requests are welcome on GitHub at https://github.com/arsduo/elm_history_tools. This project is intended to be a safe, welcoming space for collaboration, and contributors are expected to adhere to the Contributor Covenant code of conduct.

License

The gem is available as open source under the terms of the MIT License.

Code of Conduct

Everyone interacting in the ElmHistoryTools project’s codebases, issue trackers, chat rooms and mailing lists is expected to follow the Code of Conduct.